When Did Chef Pontiac Lead a Rebllion Agains the Britis

| Pontiac'due south War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars | |||||||||

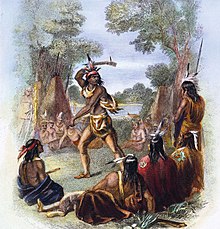

In a famous council on April 27, 1763, Pontiac urged listeners to ascent up confronting the British (19th century engraving by Alfred Bobbett) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| | Native Americans | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Jeffrey Amherst Henry Bouquet Thomas Gage | Pontiac Guyasuta | ||||||||

| Forcefulness | |||||||||

| ~3,000 soldiers[i] [ii] | ~3,500 warriors[2] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| ~450 soldiers killed[3] ~450 civilians killed[iv] ~4,000 civilians displaced[five] | 200+ warriors killed[6] civilian casualties unknown | ||||||||

Pontiac'southward War (also known as Pontiac'due south Conspiracy or Pontiac's Rebellion) was launched in 1763 by a loose confederation of Native Americans dissatisfied with British dominion in the Great Lakes region post-obit the French and Indian State of war (1754–1763). Warriors from numerous nations joined in an effort to drive British soldiers and settlers out of the region. The war is named after Odawa leader Pontiac, the most prominent of many Indigenous leaders in the conflict.

The war began in May 1763 when Native Americans, alarmed by policies imposed by British General Jeffrey Amherst, attacked a number of British forts and settlements. Eight forts were destroyed, and hundreds of colonists were killed or captured, with many more than fleeing the region. Hostilities came to an end after British Army expeditions in 1764 led to peace negotiations over the next two years. The Natives were unable to drive away the British, only the uprising prompted the British government to modify the policies that had provoked the conflict.

Warfare on the N American frontier was cruel, and the killing of prisoners, the targeting of civilians, and other atrocities were widespread.[vii] In an incident that became well-known and frequently debated, British officers at Fort Pitt attempted to infect besieging Indians with blankets that had been exposed to smallpox.[eight] The ruthlessness of the disharmonize was a reflection of a growing racial split between Ethnic peoples and British colonists.[9] The British government sought to prevent further racial violence by issuing the Royal Announcement of 1763, which created a boundary between colonists and Natives.[10]

Naming the state of war [edit]

The disharmonize is named later on its near well-known participant, the Odawa leader named Pontiac. An early name for the state of war was the "Kiyasuta and Pontiac War," "Kiaysuta" being an alternating spelling for Guyasuta, an influential Seneca/Mingo leader.[11] [12] The war became widely known as "Pontiac'due south Conspiracy" after the 1851 publication of Francis Parkman's The Conspiracy of Pontiac.[13] Parkman's book was the definitive account of the war for nearly a century and is still in print.[fourteen] [xv]

In the 20th century, some historians argued that Parkman exaggerated the extent of Pontiac'due south influence in the disharmonize, so information technology was misleading to name the war later him.[xvi] Francis Jennings (1988) wrote that "Pontiac was only a local Ottawa war chief in a 'resistance' involving many tribes."[17] Alternate titles for the war have been proposed, such equally "Pontiac's War for Indian Independence,"[18] the "Western Indians' Defensive War"[19] and "The Amerindian War of 1763."[20] Historians generally proceed to use "Pontiac's War" or "Pontiac's Rebellion," with some 21st century scholars arguing that 20th century historians had underestimated Pontiac'southward importance.[21] [22]

Origins [edit]

You think yourselves Masters of this Land, because y'all have taken it from the French, who, you lot know, had no Right to it, as information technology is the Holding of the states Indians.

Nimwha, Shawnee diplomat, to George Croghan, 1768[23]

In the decades before Pontiac's War, France and U.k. participated in a series of wars in Europe that involved the French and Indian Wars in Due north America. The largest of these wars was the worldwide Vii Years' War, in which French republic lost New France in North America to Britain. Most fighting in the North American theater of the war, generally called the French and Indian War in the Usa, or the War of Conquest (French: Guerre de la Conquête) in French Canada, came to an end after British Full general Jeffrey Amherst captured French Montréal in 1760.[24]

British troops occupied forts in the Ohio State and Great Lakes region previously garrisoned by the French. Even before the war officially ended with the Treaty of Paris (1763), the British Crown began to implement policy changes to administer its vastly expanded American territory. The French had long cultivated alliances amongst Indigenous polities, but the British post-war approach substantially treated the Ethnic nations as conquered peoples.[25] Before long, Native Americans constitute themselves dissatisfied with the British occupation.

Tribes involved [edit]

The chief surface area of activeness in Pontiac's Rebellion

Indigenous people involved in Pontiac's State of war lived in a vaguely defined region of New French republic known as the pays d'en haut ("the upper country"), which was claimed by France until the Paris peace treaty of 1763. Natives of the pays d'en haut were from many different tribal nations. These tribes were linguistic or ethnic groupings of anarchic communities rather than centralized political powers; no individual chief spoke for an entire tribe, and no nations acted in unison. For example, Ottawas did not become to war as a tribe: Some Ottawa leaders chose to do so, while other Ottawa leaders denounced the war and stayed clear of the disharmonize.[26]

The tribes of the pays d'en haut consisted of three basic groups. The outset grouping was composed of tribes of the Bang-up Lakes region: Ottawas, Ojibwes, and Potawatomis, who spoke Algonquian languages, and Hurons, who spoke an Iroquoian language. They had long been centrolineal with French habitants with whom they lived, traded, and intermarried. Great Lakes Indians were alarmed to acquire they were under British sovereignty afterwards the French loss of North America. When a British garrison took possession of Fort Detroit from the French in 1760, local Indians cautioned them that "this land was given past God to the Indians."[27] When the first Englishman reached Fort Michilimackinac, Ojibwe chief Minavavana told him "Englishman, although you take conquered the French, yous have not notwithstanding conquered us!"[28]

The second group was made up of tribes from eastern Illinois Country, which included Miamis, Weas, Kickapoos, Mascoutens, and Piankashaws.[29] Like the Swell Lakes tribes, these people had a long history of close relations with the French. Throughout the war, the British were unable to project military power into the Illinois Country, which was on the remote western edge of the disharmonize. The Illinois tribes were the last to come up to terms with the British.[30]

The third group consisted of tribes of the Ohio State: Delawares (Lenape), Shawnees, Wyandots, and Mingos. These people had migrated to the Ohio valley before in the century to escape British, French, and Iroquois domination.[31] Unlike the Great Lakes and Illinois Country tribes, Ohio tribes had no not bad attachment to the French regime, though they had fought every bit French allies in the previous state of war in an effort to drive abroad the British.[32] They made a separate peace with the British with the understanding that the British Army would withdraw. Just after the departure of the French, the British strengthened their forts rather than abandoning them, and then the Ohioans went to war in 1763 in some other attempt to drive out the British.[33]

Outside the pays d'en haut, the influential Iroquois did non, as a grouping, participate in Pontiac's War considering of their alliance with the British, known equally the Covenant Concatenation. However, the westernmost Iroquois nation, the Seneca tribe, had become disaffected with the alliance. As early equally 1761, Senecas began to ship out war messages to the Great Lakes and Ohio State tribes, urging them to unite in an attempt to drive out the British. When the war finally came in 1763, many Senecas were quick to accept activity.[34] [35]

Amherst'south policies [edit]

The policies of Full general Jeffrey Amherst, a British hero of the Seven Years' War, helped to provoke Pontiac'southward War (oil painting by Joshua Reynolds, 1765).

General Jeffrey Amherst, the British commander-in-main in North America, was in accuse of administering policy towards American Indians, which involved military matters and regulation of the fur trade. Amherst believed with France out of the picture, the Indians would have to accept British rule. He also believed they were incapable of offer any serious resistance to the British Army, and therefore, of the eight,000 troops under his command in North America, only most 500 were stationed in the region where the war erupted.[36] Amherst and officers such as Major Henry Gladwin, commander at Fort Detroit, made little effort to conceal their antipathy for Indians; those involved in the uprising frequently complained that the British treated them no better than slaves or dogs.[37]

Additional Indian resentment came from Amherst'due south decision in February 1761 to cut back on gifts given to the Indians. Gift giving had been an integral function of the human relationship between the French and the tribes of the pays d'en haut. Post-obit an Indian custom that carried of import symbolic meaning, the French gave presents (such as guns, knives, tobacco, and clothing) to village chiefs, who distributed them to their people. The chiefs gained stature this way, enabling them to maintain the brotherhood with the French.[38] The Indians regarded this every bit "a necessary office of diplomacy which involved accepting gifts in return for others sharing their lands."[39] Amherst considered this to be bribery that was no longer necessary, especially as he was nether pressure to cut expenses later on the war. Many Indians regarded this change in policy as an insult and an indication the British looked upon them as conquered people rather than every bit allies.[40] [41] [42]

Amherst too began to restrict the corporeality of armament and gunpowder that traders could sell to Indians. While the French had always made these supplies available, Amherst did not trust Indians, especially later the "Cherokee Rebellion" of 1761, in which Cherokee warriors took up artillery against their former British allies. The Cherokee war endeavor had failed due to a shortage of gunpowder; Amherst hoped hereafter uprisings could exist prevented by limiting its distribution.[43] [44] This created resentment and hardship because gunpowder and ammunition helped Indians provide food for their families and skins for the fur trade. Many Indians believed the British were disarming them as a prelude to war. Sir William Johnson, the Superintendent of the Indian Department, warned Amherst of the danger of cutting dorsum on presents and gunpowder, to no avail.[45] [46]

Land and religion [edit]

State was as well an outcome in the coming of Pontiac's War. While the French colonists had always been relatively few, there seemed to be no finish of settlers in the British colonies. Shawnees and Delawares in the Ohio Country had been displaced past British colonists in the east, and this motivated their involvement in the war. Indians in the Great Lakes region and the Illinois State had not been greatly affected by white settlement, although they were aware of the experiences of tribes in the east. Dowd (2002) argues that nigh Indians involved in Pontiac's War were not immediately threatened with displacement by white settlers, and that historians have overemphasized British colonial expansion as a cause of the state of war. Dowd believes that the presence, attitude, and policies of the British Regular army, which the Indians plant threatening and insulting, were more of import factors.[47]

Also contributing to the outbreak of war was a religious awakening which swept through Indian settlements in the early on 1760s. The motion was fed past discontent with the British too as food shortages and epidemic affliction. The most influential individual in this miracle was Neolin, known every bit the "Delaware Prophet," who called upon Indians to shun the trade goods, alcohol, and weapons of the colonists. Melding Christian doctrines with traditional Indian beliefs, Neolin said the Master of Life was displeased with Indians for taking up the bad habits of white men, and that the British posed a threat to their very existence. "If you endure the English among you," said Neolin, "you are dead men. Sickness, smallpox, and their poisonous substance [alcohol] will destroy y'all entirely."[48] It was a powerful message for a people whose world was being changed by forces that seemed beyond their command.[49]

Outbreak of war, 1763 [edit]

Planning the state of war [edit]

Pontiac has oftentimes been imagined by artists, every bit in this 19th-century painting by John Mix Stanley, but no actual portraits are known to be.[50]

Although fighting in Pontiac's War began in 1763, rumors reached British officials as early as 1761 that discontented American Indians were planning an set on. Senecas of the Ohio Land (Mingos) circulated messages ("war belts" made of wampum) calling for the tribes to course a confederacy and drive abroad the British. The Mingos, led by Guyasuta and Tahaiadoris, were concerned about being surrounded by British forts.[51] [52] [53] Similar war belts originated from Detroit and the Illinois Country.[54] The Indians were non unified, and in June 1761, natives at Detroit informed the British commander of the Seneca plot.[55] [56] William Johnson held a large council with the tribes at Detroit in September 1761, which provided a tenuous peace, but war belts continued to broadcast.[57] [58] Violence finally erupted after the Indians learned in early on 1763 of the imminent French cession of the pays d'en haut to the British.[59]

The war began at Fort Detroit under the leadership of Pontiac and chop-chop spread throughout the region. Eight British forts were taken; others, including Fort Detroit and Fort Pitt, were unsuccessfully besieged. Francis Parkman's The Conspiracy of Pontiac portrayed these attacks as a coordinated performance planned by Pontiac.[19] [lx] Parkman'south interpretation remains well known, but later on historians argued there is no clear bear witness the attacks were part of a principal plan or overall "conspiracy."[61] [note i] Rather than being planned in advance, modern scholars believe the uprising spread every bit word of Pontiac's actions at Detroit traveled throughout the pays d'en haut, inspiring discontented Indians to join the revolt. The attacks on British forts were non simultaneous: virtually Ohio Indians did not enter the war until well-nigh a month later on Pontiac began the siege at Detroit.[19]

Early historians believed French colonists had secretly instigated the war past stirring upward the Indians to make trouble for the British.[55] [63] This belief was held by British officials at the fourth dimension, but subsequent historians found no bear witness of official French involvement in the uprising.[64] [annotation two] Co-ordinate to Dowd (2002), "Indians sought French intervention and non the other fashion around."[66] Indian leaders frequently spoke of the imminent return of French ability and the revival of the Franco-Indian alliance; Pontiac even flew a French flag in his village.[67] Indian leaders obviously hoped to inspire the French to rejoin the struggle confronting the British. Although some French colonists and traders supported the uprising, the war was launched by American Indians for their own objectives.[68]

Middleton (2007) argues that Pontiac's vision, courage, persistence, and organizational abilities allowed him to activate an unprecedented coalition of Indian nations prepared to fight against the British. Tahaiadoris and Guyasuta originated the thought to proceeds independence for all Indians west of the Allegheny Mountains, although Pontiac appeared to embrace the thought past February 1763. At an emergency council meeting, he antiseptic his military support of the broad Seneca programme and worked to galvanize other tribes into the war machine operation he helped to atomic number 82, in straight contradiction to traditional Indian leadership and tribal construction. He achieved this coordination through the distribution of war belts, commencement to the northern Ojibwa and Ottawa near Michilimackinac, then to the Mingo (Seneca) on the upper Allegheny River, the Ohio Delaware near Fort Pitt, and the more westerly Miami, Kickapoo, Piankashaw, and Wea peoples.[69]

Siege of Fort Detroit [edit]

Pontiac takes up the war hatchet

Pontiac spoke at a council on the banks of the Ecorse River on April 27, 1763, about 10 miles (fifteen km) southwest of Detroit. Using the teachings of Neolin to inspire his listeners, Pontiac convinced a number of Ottawas, Ojibwas, Potawatomis, and Hurons to bring together him in an attempt to seize Fort Detroit.[70] On May 1, he visited the fort with 50 Ottawas to assess the strength of the garrison.[71] [72] According to a French chronicler, in a 2d quango Pontiac proclaimed:

It is important for the states, my brothers, that we exterminate from our lands this nation which seeks only to destroy us. You see besides every bit I that we tin can no longer supply our needs, equally we have washed from our brothers, the French.... Therefore, my brothers, we must all swear their destruction and expect no longer. Cypher prevents the states; they are few in numbers, and nosotros tin accomplish it.[73] [74]

On May 7, Pontiac entered Fort Detroit with nearly 300 men carrying concealed weapons, hoping to take the stronghold past surprise. The British had learned of his program, however, and were armed and set.[75] [note 3] His strategy foiled, Pontiac withdrew after a brief council and, two days afterwards, laid siege to the fort. He and his allies killed British soldiers and settlers they establish outside of the fort, including women and children.[77] They ritually cannibalized i of the soldiers, as was the custom in some Great Lakes Indian cultures.[78] They directed their violence at the British and generally left French colonists alone. Eventually more than 900 warriors from a half-dozen tribes joined the siege.[79]

Afterward receiving reinforcements, the British attempted to brand a surprise attack on Pontiac'south encampment. Pontiac was ready and defeated them at the Battle of Bloody Run on July 31, 1763. The state of affairs remained a stalemate at Fort Detroit, and Pontiac's influence among his followers began to wane. Groups of Indians began to carelessness the siege, some of them making peace with the British before departing. Pontiac lifted the siege on October 31, 1763, convinced that the French would non come to his help at Detroit, and removed to the Maumee River where he continued his efforts to rally resistance against the British.[80]

Pocket-size forts taken [edit]

Forts and battles of Pontiac's State of war

Before other British outposts had learned of Pontiac's siege at Detroit, Indians captured five small forts in attacks between May 16 and June 2.[81] Fort Sandusky, a modest blockhouse on the Lake Erie shore, was the first to exist taken. It had been congenital in 1761 by club of General Amherst, despite the objections of local Wyandots who warned the commander they would burn it downward.[82] [83] On May 16, 1763, a grouping of Wyandots gained entry under the pretense of holding a council, the same stratagem that had failed in Detroit ix days earlier. They seized the commander and killed 15 soldiers and a number of British traders,[84] [85] among the get-go of almost 100 traders who were killed in the early stages of the state of war.[81] They ritually scalped the dead and burned the fort to the ground, as the Wyandots had threatened a yr earlier.[84] [86]

Potawatomis captured Fort St. Joseph (site of present Niles, Michigan) on May 25, 1763, using the same method as at Sandusky. They seized the commander and killed almost of the fifteen-man garrison.[87] Fort Miami (nowadays Fort Wayne, Indiana) was the tertiary fort to fall. On May 27, the fort commander was lured out by his Indian mistress and shot dead by Miamis. The nine-man garrison surrendered after the fort was surrounded.[88]

In the Illinois Country, Weas, Kickapoos, and Mascoutens took Fort Ouiatenon, about 5 miles (8.0 km) due west of nowadays Lafayette, Indiana, on June 1, 1763. They lured soldiers outside for a council, and then took the 20-man garrison captive without bloodshed. These Indians had good relations with the British garrison, but emissaries from Pontiac had convinced them to strike. The warriors apologized to the commander for taking the fort, saying "they were Obliged to practise it by the other Nations."[89] In dissimilarity with other forts, the Indians did not kill their captives at Ouiatenon.[90]

The 5th fort to autumn, Fort Michilimackinac (present Mackinaw City, Michigan), was the largest fort taken past surprise. On June four, 1763, Ojibwas staged a game of stickball with visiting Sauks. The soldiers watched the game, every bit they had done on previous occasions. The Indians hit the ball through the open gate of the fort, then rushed in and seized weapons that Indian women had smuggled into the fort. They killed near 15 of the 35-human garrison in the struggle; they later tortured five more than to death.[91] [92] [93]

Three forts in the Ohio Country were taken in a second moving ridge of attacks in mid-June. Senecas took Fort Venango (most present Franklin, Pennsylvania) around June xvi, 1763. They killed the unabridged 12-man garrison, keeping the commander live to write down the Seneca's grievances, then burned him at the stake.[94] Possibly the same Senecas attacked Fort Le Boeuf (nowadays Waterford, Pennsylvania) on June 18, but most of the 12-homo garrison escaped to Fort Pitt.[95]

The eighth and concluding fort to autumn, Fort Presque Isle (nowadays Erie, Pennsylvania), was surrounded by about 250 Ottawas, Ojibwas, Wyandots, and Senecas on June 19. After belongings out for two days, the garrison of 30 to 60 men surrendered on the condition that they could return to Fort Pitt.[96] [97] The Indians agreed, but then took the soldiers captive, killing many.[98] [99]

Siege of Fort Pitt [edit]

Colonists in western Pennsylvania fled to the rubber of Fort Pitt subsequently the outbreak of the state of war. Nearly 550 people crowded inside, including more than 200 women and children.[100] [101] Simeon Ecuyer, the Swiss-born British officer in command, wrote that "We are and so crowded in the fort that I fear disease… the smallpox is amid us."[100] Delawares and others attacked the fort on June 22, 1763, and kept it nether siege throughout July. Meanwhile, Delaware and Shawnee war parties raided into Pennsylvania, taking captives and killing unknown numbers of settlers. Indians sporadically fired on Fort Bedford and Fort Ligonier, smaller strongholds linking Fort Pitt to the e, but they never took them.[102] [103]

Before the war, Amherst had dismissed the possibility that Indians would offer any constructive resistance to British rule, simply that summer he constitute the military situation becoming increasingly grim. He wrote the commander at Fort Detroit that captured enemy Indians should "immediately be put to death, their extirpation existence the only security for our future safety."[104] To Colonel Henry Bouquet, who was preparing to atomic number 82 an expedition to relieve Fort Pitt, Amherst wrote on nigh June 29, 1763: "Could information technology non be contrived to send the small pox amidst the disaffected tribes of Indians? Nosotros must on this occasion utilise every stratagem in our power to reduce them."[104] [105] Bouquet responded that he would attempt to spread smallpox to the Indians by giving them blankets that had been exposed to the affliction.[106] [note 4] Amherst replied to Boutonniere on July 16, endorsing the plan.[108] [109] [110] [note v]

As information technology turned out, officers at Fort Pitt had already attempted what Amherst and Bouquet were discussing, apparently without having been ordered by Amherst or Bouquet.[111] [112] [annotation 6] During a parley at Fort Pitt on June 24, Captain Ecuyer gave representatives of the besieging Delawares 2 blankets and a handkerchief that had been exposed to smallpox, hoping to spread the disease to the Indians and end the siege.[114] [115] William Trent, the fort's militia commander, wrote in his journal that "we gave them 2 Blankets and an Handkerchief out of the Pocket-size Pox Infirmary. I promise it volition have the desired upshot."[116] [117] Trent submitted an invoice to the British Army, writing that the items had been "taken from people in the Hospital to Convey the Smallpox to the Indians."[116] [117] The expense was approved by Ecuyer, and ultimately by General Thomas Gage, Amherst's successor.[117] [118]

Historian and folklorist Adrienne Mayor (1995) wrote that the smallpox blanket incident "has taken on legendary overtones every bit believers and nonbelievers continue to argue over the facts and their interpretation."[119] Peckham (1947), Jennings (1988), and Nester (2000) ended the effort to deliberately infect Indians with smallpox was successful, resulting in numerous deaths that hampered the Indian war try.[120] [121] [122] Fenn (2000) argued that "coexisting evidence" suggests the attempt was successful.[eight]

Other scholars have expressed doubts about whether the endeavor was effective. McConnell (1992) argued the smallpox outbreak amidst the Indians preceded the blanket incident, with express effect, since Indians were familiar with the disease and adept at isolating the infected.[123] Ranlet (2000) wrote that previous historians had overlooked that the Delaware chiefs who handled the blankets were in expert health a month later; he believed the attempt to infect the Indians had been a "total failure."[124] [note 7] Dixon (2005) argued that if the scheme had been successful, the Indians would have broken off the siege of Fort Pitt, but they kept it upwards for weeks afterward receiving the blankets.[126] Medical writers have expressed reservations almost the efficacy of spreading smallpox through blankets and the difficulty of determining if the outbreak was intentional or naturally occurring.[127] [128] [note 8]

Bushy Run and Devil's Hole [edit]

On August 1, 1763, well-nigh of the Indians bankrupt off the siege at Fort Pitt to intercept 500 British troops marching to the fort under Colonel Bouquet. On August 5, these two forces met at the Battle of Bushy Run. Although his force suffered heavy casualties, Bouquet fought off the attack and relieved Fort Pitt on August 20, bringing the siege to an end. His victory at Bushy Run was celebrated by the British; church building bells rang through the dark in Philadelphia, and King George praised him.[130]

This victory was followed past a costly defeat. Fort Niagara, i of the well-nigh important western forts, was not assaulted, but on September 14, 1763, at least 300 Senecas, Ottawas, and Ojibwas attacked a supply train along the Niagara Falls portage. Ii companies sent from Fort Niagara to rescue the supply train were also defeated. More than than seventy soldiers and teamsters were killed in these actions, which colonists dubbed the "Devil's Hole Massacre," the deadliest date for British soldiers during the state of war.[131] [132] [133]

Paxton Boys [edit]

Massacre of the Indians at Lancaster past the Paxton Boys in 1763, lithograph published in Events in Indian History (John Wimer, 1841)

The violence and terror of Pontiac'south War convinced many western Pennsylvanians that their government was not doing enough to protect them. This discontentment was manifested most seriously in an insurgence led past a vigilante group known every bit the Paxton Boys, so-called because they were primarily from the surface area around the Pennsylvania hamlet of Paxton (or Paxtang). The Paxtonians turned their anger towards American Indians—many of them Christians—who lived peacefully in small enclaves in the midst of white Pennsylvania settlements. Prompted by rumors that an Indian state of war party had been seen at the Indian village of Conestoga, on December 14, 1763, a group of more than than fifty Paxton Boys marched on the village and murdered the six Susquehannocks they found there. Pennsylvania officials placed the remaining 14 Susquehannocks in protective custody in Lancaster, but on December 27, the Paxton Boys broke into the jail and killed them. Governor John Penn issued bounties for the arrest of the murderers, but no i came forrad to place them.[134]

The Paxton Boys then set their sights on other Indians living within eastern Pennsylvania, many of whom fled to Philadelphia for protection. Several hundred Paxtonians marched on Philadelphia in January 1764, where the presence of British troops and Philadelphia militia prevented them from committing more than violence. Benjamin Franklin, who had helped organize the militia, negotiated with the Paxton leaders and brought an terminate to the crisis. Later, Franklin published a scathing indictment of the Paxton Boys. "If an Indian injures me," he asked, "does it follow that I may revenge that Injury on all Indians?"[135]

British response, 1764–1766 [edit]

Indian raids on frontier settlements escalated in the spring and summer of 1764. The hardest hit colony was Virginia, where more than than 100 settlers were killed.[136] On May 26 in Maryland, 15 colonists working in a field almost Fort Cumberland were killed. On June 14, almost 13 settlers well-nigh Fort Loudoun in Pennsylvania were killed and their homes burned. The most notorious raid occurred on July 26, when four Delaware warriors killed and scalped a schoolhouse teacher and ten children in what is now Franklin County, Pennsylvania. Incidents such as these prompted the Pennsylvania Assembly, with the approving of Governor Penn, to reintroduce the scalp bounties offered during the French and Indian State of war, which paid coin for every enemy Indian killed above the historic period of 10, including women.[136] [137]

General Amherst, held responsible for the uprising by the Board of Trade, was recalled to London in Baronial 1763 and replaced by Major General Thomas Gage. In 1764, Gage sent 2 expeditions into the west to crush the rebellion, rescue British prisoners, and arrest the Indians responsible for the war. According to historian Fred Anderson, Cuff'southward campaign, which had been designed by Amherst, prolonged the state of war for more than a yr because it focused on punishing the Indians rather than ending the war. Gage's one significant departure from Amherst's plan was to let William Johnson to deport a peace treaty at Niagara, giving Indians an opportunity to "coffin the hatchet."[138]

Fort Niagara treaty [edit]

From July to August 1764, Johnson conducted a treaty at Fort Niagara with about two,000 Indians in attendance, primarily Iroquois. Although nigh Iroquois had stayed out of the war, Senecas from the Genesee River valley had taken upward arms against the British, and Johnson worked to bring them back into the Covenant Chain alliance. As restitution for the Devil's Hole ambush, the Senecas were compelled to cede the strategically of import Niagara portage to the British. Johnson even convinced the Iroquois to ship a war political party confronting the Ohio Indians. This Iroquois trek captured a number of Delawares and destroyed abandoned Delaware and Shawnee towns in the Susquehanna Valley, only otherwise the Iroquois did not contribute to the war effort as much as Johnson had desired.[139] [140] [141]

2 expeditions [edit]

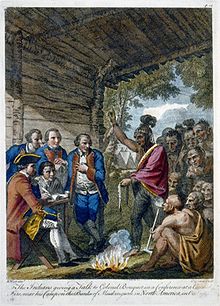

Bouquet'south negotiations are depicted in this 1765 engraving based on a painting past Benjamin W. The Indian orator holds a belt of wampum, essential for diplomacy in the Eastern Woodlands.

Having secured the expanse around Fort Niagara, the British launched two military expeditions into the west. The first trek, led by Colonel John Bradstreet, was to travel by boat across Lake Erie and reinforce Detroit. Bradstreet was to subdue the Indians around Detroit before marching southward into the Ohio Country. The second expedition, commanded by Colonel Boutonniere, was to march west from Fort Pitt and form a second front in the Ohio Country.

Bradstreet left Fort Schlosser in early August 1764 with about 1,200 soldiers and a big contingent of Indian allies enlisted by Sir William Johnson. Bradstreet felt that he did not take enough troops to subdue enemy Indians by force, and so when strong winds on Lake Erie forced him to terminate at Fort Presque Isle on August 12, he decided to negotiate a treaty with a delegation of Ohio Indians led past Guyasuta. Bradstreet exceeded his authority by conducting a peace treaty rather than a simple truce, and by agreeing to halt Bouquet's expedition, which had non withal left Fort Pitt. Gage, Johnson, and Bouquet were outraged when they learned what Bradstreet had done. Gage rejected the treaty, believing that Bradstreet had been duped into abandoning his offensive in the Ohio Country. Gage may take been correct: the Ohio Indians did not return prisoners as promised in a second coming together with Bradstreet in September, and some Shawnees were trying to enlist French aid in order to continue the war.[142] [143] [144] [145]

Bradstreet continued westward, unaware his unauthorized diplomacy was angering his superiors. He reached Fort Detroit on Baronial 26, where he negotiated some other treaty. In an attempt to discredit Pontiac, who was not present, Bradstreet chopped up a peace belt Pontiac had sent to the meeting. According to historian Richard White, "such an human activity, roughly equivalent to a European ambassador's urinating on a proposed treaty, had shocked and offended the gathered Indians." Bradstreet also claimed the Indians had accepted British sovereignty as a issue of his negotiations, just Johnson believed this had not been fully explained to the Indians and that farther councils would be needed. Bradstreet had successfully reinforced and reoccupied British forts in the region, but his diplomacy proved to exist controversial and inconclusive.[146] [147] [148]

Colonel Bouquet, delayed in Pennsylvania while mustering the militia, finally set out from Fort Pitt on Oct 3, 1764, with 1,150 men. He marched to the Muskingum River in the Ohio Land, within striking altitude of a number of Indian villages. Treaties had been negotiated at Fort Niagara and Fort Detroit, so the Ohio Indians were isolated and, with some exceptions, ready to make peace. In a council which began on October 17, Bouquet demanded that the Ohio Indians render all captives, including those not yet returned from the French and Indian State of war. Guyasuta and other leaders reluctantly handed over more than 200 captives, many of whom had been adopted into Indian families. Not all of the captives were present, so the Indians were compelled to give up hostages as a guarantee that the other captives would be returned. The Ohio Indians agreed to attend a more formal peace briefing with William Johnson, which was finalized in July 1765.[149] [150] [151]

Treaty with Pontiac [edit]

Although the military disharmonize essentially concluded with the 1764 expeditions,[152] Indians withal called for resistance in the Illinois Country, where British troops had yet to take possession of Fort de Chartres from the French. A Shawnee war main named Charlot Kaské emerged as the nearly strident anti-British leader in the region, temporarily surpassing Pontiac in influence. Kaské traveled equally far south as New Orleans in an effort to enlist French help against the British.[153] [154] [155]

In 1765, the British decided that the occupation of the Illinois State could only exist accomplished by diplomatic means. Equally Gage commented to one of his officers, he was determined to take "none our enemy" among the Indian peoples, and that included Pontiac, to whom he now sent a wampum belt suggesting peace talks. Pontiac had get less militant after hearing of Bouquet's truce with the Ohio state Indians.[156] [157] Johnson'south deputy, George Croghan, appropriately traveled to the Illinois country in the summer of 1765, and although he was injured forth the way in an assail by Kickapoos and Mascoutens, he managed to meet and negotiate with Pontiac. While Charlot Kaské wanted to fire Croghan at the stake,[158] Pontiac urged moderation and agreed to travel to New York, where he made a formal treaty with William Johnson at Fort Ontario on July 25, 1766. It was hardly a surrender: no lands were ceded, no prisoners returned, and no hostages were taken.[159] Rather than accept British sovereignty, Kaské left British territory by crossing the Mississippi River with other French and Native refugees.[160]

Aftermath [edit]

Considering many children taken as captives had been adopted into Native families, their forced render oftentimes resulted in emotional scenes, as depicted in this engraving based on a painting past Benjamin West.

The total loss of life resulting from Pontiac's State of war is unknown. Virtually 400 British soldiers were killed in action and maybe 50 were captured and tortured to death.[iii] [161] George Croghan estimated that 2,000 settlers had been killed or captured,[162] a figure sometimes repeated as two,000 settlers killed.[163] [164] [note 9] [note x] The violence compelled approximately 4,000 settlers from Pennsylvania and Virginia to flee their homes.[5] American Indian losses went more often than not unrecorded, just it has been estimated at least 200 warriors were killed in battle,[vi] with additional deaths if germ warfare initiated at Fort Pitt was successful.[4] [165]

Pontiac's State of war has traditionally been portrayed as a defeat for the Indians,[166] but scholars now usually view it equally a military stalemate: while the Indians had failed to drive away the British, the British were unable to conquer the Indians. Negotiation and accommodation, rather than success on the battlefield, ultimately brought an finish to the war.[167] [168] [169] The Indians had won a victory of sorts by compelling the British authorities to carelessness Amherst'south policies and create a human relationship with the Indians modeled on the Franco-Indian alliance.[170] [171] [172]

Relations between British colonists and American Indians, which had been severely strained during the French and Indian War, reached a new low during Pontiac's State of war.[173] According to Dixon (2005), "Pontiac's State of war was unprecedented for its atrocious violence, equally both sides seemed intoxicated with genocidal fanaticism."[7] Richter (2001) characterizes the Indian attempt to drive out the British, and the attempt of the Paxton Boys to eliminate Indians from their midst, every bit parallel examples of indigenous cleansing.[174] People on both sides of the conflict had come up to the decision that colonists and natives were inherently different and could non alive with each other. According to Richter, the war saw the emergence of "the novel idea that all Native people were 'Indians,' that all Euro-Americans were 'Whites,' and that all on one side must unite to destroy the other."[9]

The British government also came to the conclusion that colonists and Indians must exist kept apart. On October 7, 1763, the Crown issued the Regal Annunciation of 1763, an effort to reorganize British N America after the Treaty of Paris. The Proclamation, already in the works when Pontiac'due south War erupted, was hurriedly issued after news of the uprising reached London. Officials drew a boundary line between the British colonies and American Indian lands west of the Appalachian Mountains, creating a vast "Indian Reserve" that stretched from the Appalachians to the Mississippi River and from Florida to Quebec. By forbidding colonists from trespassing on Indian lands, the British government hoped to avoid more conflicts like Pontiac'south War. "The Royal Proclamation," writes Calloway (2006), "reflected the notion that segregation not interaction should characterize Indian-white relations."[10]

The furnishings of Pontiac's War were long-lasting. Because the Announcement officially recognized that indigenous people had certain rights to the lands they occupied, it has been called a Native American "Bill of Rights," and withal informs the relationship between the Canadian authorities and First Nations.[175] For British colonists and land speculators, nevertheless, the Proclamation seemed to deny them the fruits of victory—western lands—that had been won in the state of war with French republic. This created resentment, undermining colonial attachment to the Empire and contributing to the coming of the American Revolution.[176] According to Calloway, "Pontiac's Revolt was not the last American war for independence—American colonists launched a rather more successful try a dozen years later, prompted in part by the measures the British government took to effort to forbid another war like Pontiac's."[177]

For American Indians, Pontiac's War demonstrated the possibilities of pan-tribal cooperation in resisting Anglo-American colonial expansion. Although the conflict divided tribes and villages,[178] the war too saw the first all-encompassing multi-tribal resistance to European colonization in North America,[179] and the first war between Europeans and American Indians that did not end in complete defeat for the Indians.[180] The Declaration of 1763 ultimately did non prevent British colonists and land speculators from expanding westward, and so Indians found it necessary to class new resistance movements. Offset with conferences hosted by Shawnees in 1767, in the following decades leaders such equally Joseph Brant, Alexander McGillivray, Blue Jacket, and Tecumseh would attempt to forge confederacies that would revive the resistance efforts of Pontiac's War.[181] [182]

References [edit]

Notes [edit]

- ^ Jacobs supported Parkman'southward thesis that Pontiac planned the war in advance, but objected to calling information technology a "conspiracy" because it suggested Indian grievances were unjustified.[62]

- ^ The rumor of French instigation arose in part because French state of war belts from the Seven Years' War were yet in circulation.[65]

- ^ Major Gladwin, the fort's commander, did non reveal who warned him of Pontiac's plan; historians place several possibilities.[76]

- ^ Bouquet to Amherst, July 13: "I will try to inoculate the bastards with some blankets that may fall into their hands, and take care not to get the disease myself."[107]

- ^ Amherst to Boutonniere, July xvi: "You will do well to inoculate the Indians by means of blankets, likewise as every other method that tin can serve to extirpate this execrable race."[107]

- ^ "Neither Amherst nor Bouquet really tried germ warfare. The attempt to disseminate smallpox took place at Fort Pitt independent of both of them."[113]

- ^ "Deliberately trying to spread affliction is despicable in whatever century information technology might take place, but the smallpox incident has been blown out of all proportion, given that it was likely a total failure."[125]

- ^ "Notwithstanding, in the lite of contemporary noesis, information technology remains doubtful whether [Ecuyer's] hopes were fulfilled, given the fact that the transmission of smallpox through this kind of vector is much less efficient than respiratory transmission…."[129]

- ^ Nester later revises this number down to about 450 settlers killed.[4]

- ^ Dowd argues that Croghan's widely reported judge "cannot exist taken seriously" because it was a "wild approximate" made while Croghan was far abroad in London.[162]

Citations [edit]

- ^ Dixon 2005, p. 158.

- ^ a b Dowd 2002, p. 117.

- ^ a b Peckham 1947, p. 239.

- ^ a b c Nester 2000, p. 279.

- ^ a b Dowd 2002, p. 275.

- ^ a b Middleton 2007, p. 202.

- ^ a b Dixon 2005, p. xiii.

- ^ a b Fenn 2000, p. 1558.

- ^ a b Richter 2001, p. 208.

- ^ a b Calloway 2006, p. 92.

- ^ Dixon 2005, p. 303n21.

- ^ Peckham 1947, p. 107n.

- ^ Nester 2000, p. x.

- ^ McConnell 1994, p. xiii.

- ^ Dowd 2002, p. 7.

- ^ Middleton 2006, pp. 2–iii.

- ^ Jennings 1988, p. 442.

- ^ Jacobs 1972, p. 93.

- ^ a b c McConnell 1992, p. 182.

- ^ Steele 1994, p. 235.

- ^ Dixon 2005, p. 131.

- ^ Middleton 2006, pp. 1–32.

- ^ Dowd 2002, p. 216.

- ^ Anderson 2000, p. 453.

- ^ White 1991, p. 256.

- ^ White 1991, pp. fourteen, 287.

- ^ White 1991, p. 260.

- ^ Skaggs 2001, p. 1.

- ^ Dowd 2002, p. 168.

- ^ Anderson 2000, pp. 626–32.

- ^ McConnell 1992, pp. v–20.

- ^ White 1991, pp. 240–45.

- ^ White 1991, pp. 248–55.

- ^ Dixon 2005, pp. 85–89.

- ^ Middleton 2007, pp. 96–99.

- ^ Dixon 2005, pp. 157–58.

- ^ Dowd 2002, pp. 63–69.

- ^ White 1991, pp. 36, 113, 179–83.

- ^ Borrows 1997, p. 170.

- ^ White 1991, pp. 256–58.

- ^ McConnell 1992, pp. 163–64.

- ^ Dowd 2002, pp. 70–75.

- ^ Anderson 2000, pp. 468–71.

- ^ Dixon 2005, p. 78.

- ^ Dowd 2002, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Dixon 2005, p. 83.

- ^ Dowd 2002, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Dowd 1992, p. 34.

- ^ White 1991, pp. 279–85.

- ^ Dowd 2002, p. six.

- ^ White 1991, p. 272.

- ^ Dixon 2005, pp. 85–87.

- ^ Middleton 2007, pp. 33–46.

- ^ White 1991, p. 276.

- ^ a b Dowd 2002, p. 105.

- ^ Dixon 2005, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Dixon 2005, pp. 92–93, 100.

- ^ Nester 2000, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Dixon 2005, p. 104.

- ^ Parkman 1870, pp. 1:186–87.

- ^ Peckham 1947, pp. 108–ten.

- ^ Jacobs 1972, pp. 83–90.

- ^ Peckham 1947, p. 105.

- ^ Dowd 2002, pp. 105–13.

- ^ White 1991, pp. 276–77.

- ^ Dowd 2002, p. 121.

- ^ Dowd 2002, p. 160.

- ^ Calloway 2006, p. 126.

- ^ Middleton 2007, pp. 68–73.

- ^ Parkman 1870, pp. 1:200–08.

- ^ Dixon 2005, p. 108.

- ^ Peckham 1947, p. 116.

- ^ Peckham 1947, pp. 119–twenty.

- ^ Dixon 2005, p. 109.

- ^ Nester 2000, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Dixon 2005, pp. 109–x.

- ^ Dixon 2005, pp. 111–12.

- ^ Dixon 2005, p. 114.

- ^ Anderson 2000, p. 538.

- ^ Dowd 2002, p. 139.

- ^ a b Dowd 2002, p. 125.

- ^ McConnell 1992, p. 167.

- ^ Nester 2000, p. 44.

- ^ a b Nester 2000, p. 86.

- ^ Dixon 2005, p. 119.

- ^ Parkman 1870, p. i:271.

- ^ Nester 2000, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Nester 2000, p. 90.

- ^ Dixon 2005, p. 121.

- ^ Nester 2000, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Dixon 2005, p. 122.

- ^ Dowd 2002, p. 126.

- ^ Nester 2000, pp. 95–97.

- ^ Nester 2000, p. 99.

- ^ Nester 2000, pp. 101–02.

- ^ Dowd 2002, p. 127.

- ^ Dixon 2005, p. 149.

- ^ Dowd 2002, p. 128.

- ^ Middleton 2007, pp. 98–99.

- ^ a b Dixon 2005, p. 151.

- ^ Nester 2000, p. 92.

- ^ Dowd 2002, p. 130.

- ^ Nester 2000, p. 130.

- ^ a b Peckham 1947, p. 226.

- ^ Anderson 2000, pp. 542, 809n11.

- ^ Fenn 2000, pp. 1555–56.

- ^ a b Anderson 2000, p. 809n11.

- ^ Fenn 2000, pp. 1556–57.

- ^ Grenier 2005, pp. 144–45.

- ^ Nester 2000, pp. 114–fifteen.

- ^ Anderson 2000, p. 542.

- ^ Fenn 2000, p. 1557.

- ^ Ranlet 2000, p. 431.

- ^ Anderson 2000, p. 541.

- ^ Jennings 1988, p. 447n26.

- ^ a b Ranlet 2000, p. 428.

- ^ a b c Fenn 2000, p. 1554.

- ^ Ranlet 2000, p. 430.

- ^ Mayor 1995, p. 57.

- ^ Peckham 1947, p. 170.

- ^ Jennings 1988, pp. 447–48.

- ^ Nester 2000, p. 112.

- ^ McConnell 1992, pp. 195–96.

- ^ Ranlet 2000, pp. 434, 438.

- ^ Ranlet 2000, p. 438.

- ^ Dixon 2005, p. 154–55.

- ^ Dembek 2007, pp. 2–three.

- ^ Barras & Greub 2014.

- ^ Barras & Greub 2014, p. 499.

- ^ Dixon 2005, p. 196.

- ^ Peckham 1947, pp. 224–25.

- ^ Dixon 2005, p. 210–11.

- ^ Dowd 2002, p. 137.

- ^ Nester 2000, p. 173.

- ^ Nester 2000, p. 176.

- ^ a b Nester 2000, p. 194.

- ^ Dixon 2005, pp. 222–24.

- ^ Anderson 2000, pp. 553, 617–20.

- ^ McConnell 1992, pp. 197–99.

- ^ Dixon 2005, pp. 219–xx, 228.

- ^ Dowd 2002, pp. 151–53.

- ^ White 1991, pp. 291–92.

- ^ McConnell 1992, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Dixon 2005, pp. 228–29.

- ^ Dowd 2002, pp. 155–58.

- ^ White 1991, pp. 297–98.

- ^ Dixon 2005, pp. 227–32.

- ^ Dowd 2002, pp. 153–62.

- ^ McConnell 1992, pp. 201–05.

- ^ Dixon 2005, pp. 233–41.

- ^ Dowd 2002, pp. 162–65.

- ^ Dixon 2005, p. 242.

- ^ White 1991, pp. 300–01.

- ^ Dowd 2002, pp. 217–nineteen.

- ^ Middleton 2007, pp. 183–99.

- ^ Middleton 2007, p. 189.

- ^ White 1991, p. 302.

- ^ White 1991, p. 305n70.

- ^ Dowd 2002, pp. 253–54.

- ^ Calloway 2006, pp. 76, 150.

- ^ Nester 2000, p. 280.

- ^ a b Dowd 2002, p. 142.

- ^ Jennings 1988, p. 446.

- ^ Nester 2000, pp. vii, 172.

- ^ Fenn 2000, pp. 1557–58.

- ^ Peckham 1947, p. 322.

- ^ Dixon 2005, pp. 242–43.

- ^ White 1991, p. 289.

- ^ McConnell 1994, p. 15.

- ^ White 1991, pp. 305–09.

- ^ Calloway 2006, p. 76.

- ^ Richter 2001, p. 210.

- ^ Calloway 2006, p. 77.

- ^ Richter 2001, pp. 190–91.

- ^ Calloway 2006, pp. 96–98.

- ^ Dixon 2005, p. 246.

- ^ Calloway 2006, p. 91.

- ^ Hinderaker 1997, p. 156.

- ^ Steele 1994, p. 234.

- ^ Steele 1994, p. 247.

- ^ Dowd 1992, pp. 42–43, 91–93.

- ^ Dowd 2002, pp. 264–66.

Sources [edit]

- Anderson, Fred (2000). Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766. New York: Knopf. ISBN0-375-40642-5.

- Barras, 5; Greub, M (2014). "History of biological warfare and bioterrorism". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. twenty (6): 497–502. doi:ten.1111/1469-0691.12706. PMID 24894605.

- Borrows, John (1997). "Wampum at Niagara: The Royal Proclamation, Canadian Legal History, and Self Government" (PDF). In Asch, Michael (ed.). Ancient and Treaty Rights in Canada: Essays on Law, Equity, and Respect for Deviation. Vancouver: UBC Press. pp. 169–72. ISBN978-0-7748-0581-0.

- Calloway, Colin (2006). The Scratch of a Pen: 1763 and the Transformation of Northward America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN0-xix-530071-viii.

- Dembek, Zygmunt F., ed. (2007). Medical Aspects of Biological Warfare. Government Press Office. ISBN978-0-16-087238-9.

- Dixon, David (2005). Never Come to Peace Again: Pontiac's Uprising and the Fate of the British Empire in North America. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN0-8061-3656-1.

- Dowd, Gregory Evans (1992). A Spirited Resistance: The Northward American Indian Struggle for Unity, 1745–1815. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN0-8018-4609-nine.

- Dowd, Gregory Evans (2002). War under Heaven: Pontiac, the Indian Nations, & the British Empire. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN0-8018-7079-8.

- Fenn, Elizabeth A. (2000). "Warfare in Eighteenth-Century North America: Beyond Jeffery Amherst". The Journal of American History. 86 (four): 1552–1580. doi:10.2307/2567577. JSTOR 2567577.

- Grenier, John (2005). The First Manner of State of war: American State of war Making on the Borderland, 1607–1814. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing. ISBN0-521-84566-1.

- Hinderaker, Eric (1997). Elusive Empires: Constructing Colonialism in the Ohio Valley, 1763–1800. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press. ISBN0-521-66345-8.

- Jacobs, Wilbur R (1972). "Pontiac'southward State of war—A Conspiracy?". Dispossessing the American Indian: Indians and Whites on the Colonial Frontier. New York: Scribners. pp. 83–93. ISBN978-0806119359.

- Jennings, Francis (1988). Empire of Fortune: Crowns, Colonies, and Tribes in the Seven Years War in America' . New York: Norton. ISBN0-393-30640-ii.

- Mayor, Adrienne (1995). "The Nessus Shirt in the New Earth: Smallpox Blankets in History and Legend". The Journal of American Folklore. 108 (427): 54–77. doi:10.2307/541734. JSTOR 541734. Retrieved January xv, 2021.

- McConnell, Michael Northward. (1992). A Country Betwixt: The Upper Ohio Valley and Its Peoples, 1724–1774. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN0-8032-8238-9.

- McConnell, Michael N. (1994). "Introduction to the Bison Book Edition" of The Conspiracy of Pontiac by Francis Parkman . Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN0-8032-8733-Ten.

- Middleton, Richard (2006). "Pontiac: Local Warrior or Pan Indian Leader?". Michigan Historical Review. 32 (two): i–32. doi:10.1353/mhr.2006.0028.

- Middleton, Richard (2007). Pontiac's State of war: Its Causes, Form, and Consequences. New York: Routledge. ISBN978-0-415-97913-9.

- Nester, William R. (2000). "Haughty Conquerors": Amherst and the Great Indian Uprising of 1763. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN0-275-96770-0.

- Parkman, Francis (1870). The Conspiracy of Pontiac and the Indian War afterwards the Conquest of Canada (1994 reprint of tenth revised ed.). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Printing. ISBN0-8032-8733-Ten. Parkman'southward landmark two-volume work, originally published in 1851, subsequently revised and oft reprinted, has largely been supplanted by modern scholarship.

- Peckham, Howard H. (1947). Pontiac and the Indian Uprising. Chicago: Academy of Chicago Printing. ISBN0-8143-2469-X.

- Ranlet, Philip (2000). "The British, the Indians, and Smallpox: What Actually Happened at Fort Pitt in 1763?". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 67 (3): 427–441. JSTOR 27774278. Retrieved January xiii, 2021.

- Richter, Daniel K. (2001). Facing East from Indian State: A Native History of Early America. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN0-674-00638-0.

- Skaggs, David Curtis; Nelson, Larry Fifty., eds. (2001). The Lx Years' State of war for the Great Lakes, 1754–1814. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. ISBN0-87013-569-4.

- Steele, Ian One thousand. (1994). Warpaths: Invasions of North America. New York: Oxford University Printing. ISBN0-xix-508223-0.

- White, Richard (1991). The Center Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Groovy Lakes Region, 1650–1815. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing. ISBN0-521-42460-7.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pontiac%27s_War

0 Response to "When Did Chef Pontiac Lead a Rebllion Agains the Britis"

Post a Comment